Thousands of international students flock to German universities each year – drawn by the excellent infrastructure, superb teaching staff and, of course, the free (or nearly free education). But a report by the Körber Institute says they are the last country to still have policies on providing tuition-free education to nearly all students.

What’s it like to study in Germany?

Coming from a bachelor degree in the US, I can tell you from a first-person perspective that my Master studies in Germany not only met, but exceeded the level of personal attention and growth I received – for a fraction of the cost. As college tuition in the US – and across the globe – continues to rise, a degree is Germany is becoming a more realistic option.

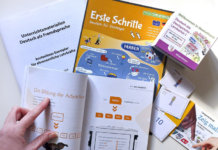

Many students may be surprised to know you don’t have to speak German to enroll in a German university. On the contrary, public universities are creating more and more English-only programs each year.

Why?

The scope of these programs tends to be in fields specifically related to globalization – business, technology, design, etc. Philosophy, for example, is still understandably taught in the mother tongue. Creating these programs in English allows German students to be better prepared to work in ever globalizing job market. Secondly, by providing programs in English, this opens up the pool to talented students from all over the globe.

There are more than 25,000 international students studying in Berlin – that’s roughly €332.5 million that the city spends on foreign students each year

According to Berlin’s Secretary of Science Steffen Krach, that’s not a problem.

“It’s not unattractive for us when knowledge and know-how come to us from other countries and result in jobs when these students have a business idea and stay in Berlin to create their start-up.”

Research finds that 50% of these students end up staying in Germany. “Even if people don’t pay tuition fees, if only 40% stay for five years and pay taxes we recover the cost for the tuition and for the study places so that works out well,” says Sebastian Fohrbeck of the DAAD.

As well, this helps to provide a solution to Germany’s increasing demographic problem – a growing retired population and fewer young people entering the workforce.

“Keeping international students who have studied in the country is the ideal way of immigration. They have the needed certificates, they don’t have a language problem at the end of their stay and they know the culture,” says Fohrbeck.